according to hans selye, what happens when an animal is alarmed?

Chapter xi. Emotions and Motivations

xi.two Stress: The Unseen Killer

Learning Objectives

- Define stress and review the body's physiological responses to it.

- Summarize the negative health consequences of prolonged stress.

- Explain the differences in how people answer to stress.

- Review the methods that are successful in coping with stress.

Emotions matter because they influence our behaviour. And there is no emotional feel that has a more than powerful influence on us than stress. Stress refers to the physiological responses that occur when an organism fails to reply appropriately to emotional or physical threats (Selye, 1956). Extreme negative events, such as being the victim of a terrorist attack, a natural disaster, or a violent law-breaking, may produce an extreme form of stress known as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a medical syndrome that includes symptoms of feet, sleeplessness, nightmares, and social withdrawal. PTSD is frequently experienced by victims or witnesses of violence or abuse, natural disasters, major accidents, or war.

When it is farthermost or prolonged, stress can create substantial wellness problems. A written report out of the University of British Columbia found that emergency personnel such every bit doctors, nurses, paramedics, and firefighters experience mail-traumatic stress at twice the rate of the average population. In Canada, it is estimated that up to x% of war zone veterans — including war service veterans and peacekeeping forces — will experience mail service-traumatic stress disorder (CMHA, 2014). People in New York City who lived nearer to the site of the ix/11 terrorist attacks reported experiencing more stress in the year post-obit it than those who lived farther away (Pulcino et al., 2003). But stress is non unique to the feel of extremely traumatic events. Information technology can too occur, and have a variety of negative outcomes, in our everyday lives.

The Negative Effects of Stress

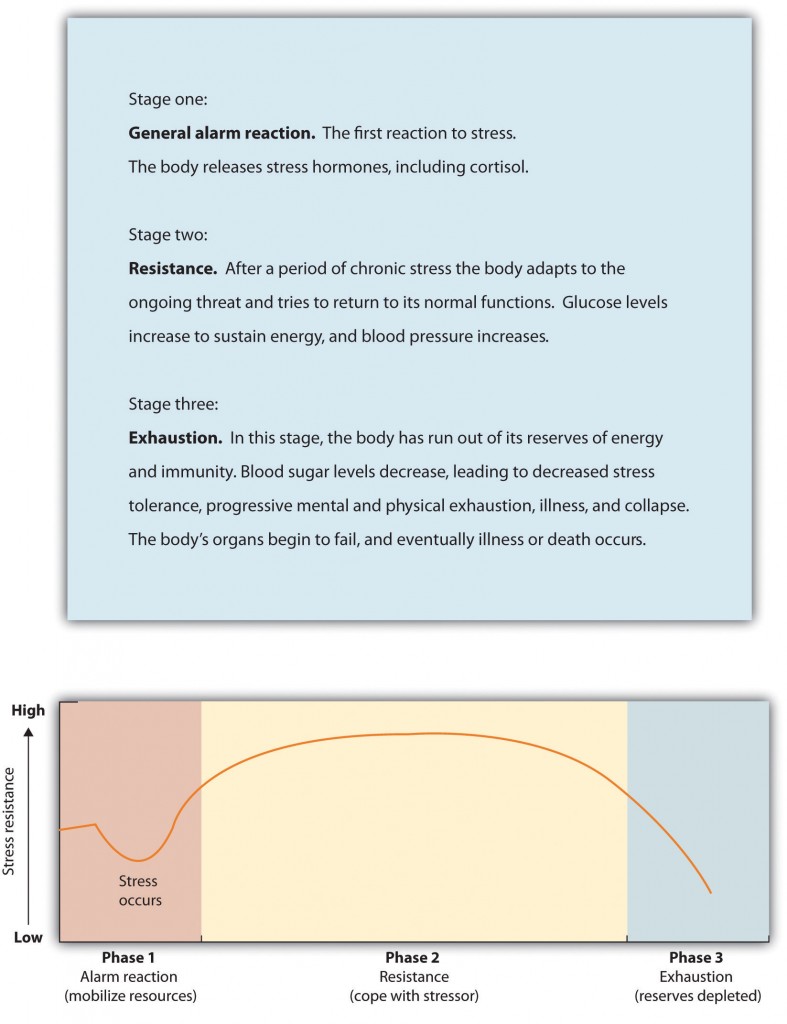

The physiologist Hans Selye (1907-1982) studied stress by examining how rats responded to being exposed to stressors such every bit farthermost cold, infection, shock, or excessive practise (Selye, 1936, 1974, 1982). Selye plant that regardless of the source of the stress, the rats experienced the same series of physiological changes as they suffered the prolonged stress. Selye created the term general accommodation syndrome to refer to the three distinct phases of physiological modify that occur in response to long-term stress: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion (Figure 11.7, "Full general Adaptation Syndrome").

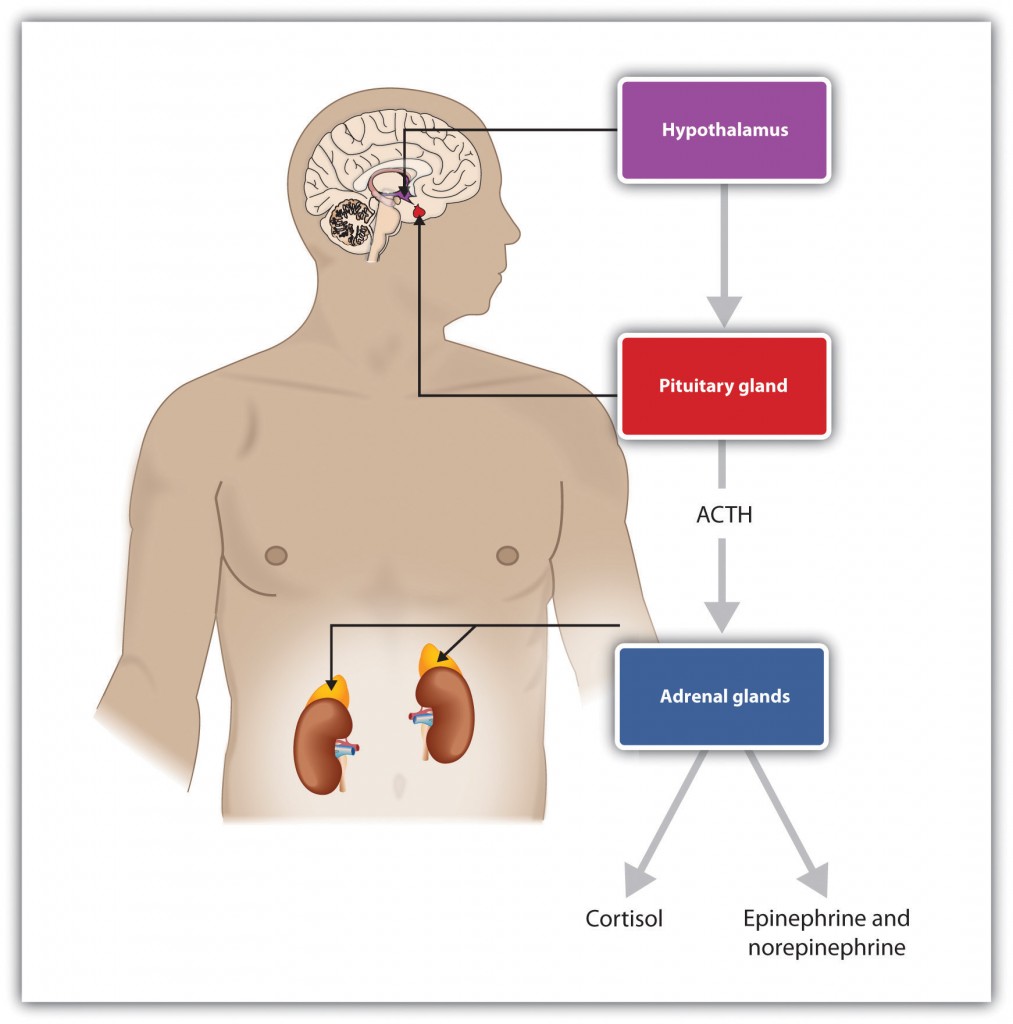

The experience of stress creates both an increase in full general arousal in the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), equally well as another, even more complex, system of physiological changes through the HPA axis. The HPA centrality is a physiological response to stress involving interactions among the (H) hypothalamus, the (P) pituitary, and the (A) adrenal glands (Effigy 11.8, "HPA Axis"). The HPA response begins when the hypothalamus secretes releasing hormones that direct the pituitary gland to release the hormone ACTH. ACTH then directs the adrenal glands to secrete more hormones, including epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol, a stress hormone that releases sugars into the blood, helping preparing the trunk to respond to threat (Rodrigues, LeDoux, & Sapolsky, 2009).

The initial arousal that accompanies stress is normally quite adaptive because information technology helps us reply to potentially dangerous events. The feel of prolonged stress, however, has a direct negative influence on our concrete health, because at the same time that stress increases activity in the sympathetic division of the ANS, it also suppresses activity in the parasympathetic division of the ANS. When stress is long term, the HPA axis remains active and the adrenals continue to produce cortisol. This increased cortisol production exhausts the stress mechanism, leading to fatigue and depression.

The HPA reactions to persistent stress lead to a weakening of the immune system, making the states more susceptible to a variety of wellness problems including colds and other diseases (Cohen & Herbert, 1996; Faulkner & Smith, 2009; Miller, Chen, & Cole, 2009; Uchino, Smith, Holt-Lunstad, Campo, & Reblin, 2007). Stress likewise amercement our Deoxyribonucleic acid, making us less likely to exist able to repair wounds and respond to the genetic mutations that cause disease (Epel et al., 2006). As a result, wounds heal more slowly when we are under stress, and we are more likely to become cancer (Kiecolt-Glaser, McGuire, Robles, & Glaser, 2002; Wells, 2006).

Chronic stress is also a major contributor to centre affliction. Although heart disease is caused in function by genetic factors, as well every bit high blood pressure, loftier cholesterol, and cigarette smoking, it is too caused by stress (Krantz & McCeney, 2002). Long-term stress creates two opposite effects on the coronary system. Stress increases cardiac output (i.due east., the heart pumps more blood) at the same time that information technology reduces the ability of the claret vessels to conduct blood through the arteries, as the increase in levels of cortisol leads to a buildup of plaque on artery walls (Dekker et al., 2008). The combination of increased blood flow and arterial constriction leads to increased blood force per unit area (hypertension), which tin damage the center muscle, leading to heart assault and death.

Stressors in Our Everyday Lives

The stressors for Selye'south rats included electric stupor and exposure to common cold. Although these are probably not on your top-10 listing of most common stressors, the stress that you feel in your everyday life tin also be taxing. Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe (1967) developed a mensurate of some everyday life events that might lead to stress, and you can appraise your own likely stress level by completing the measure in Table xi.ii, "The Holmes and Rahe Stress Calibration." Yous might want to pay particular attention to this score, considering information technology tin can predict the likelihood that yous will get ill. Rahe and colleagues examined the medical records of over five,000 patients to determine whether stressful events might crusade illnesses. Patients were asked to tally a list of 43 life events based on a relative score. A positive correlation of 0.118 was found between their life events and their illnesses resulting in the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) (Rahe, Mahan, Arthur, & Gunderson, 1970). Rahe and colleagues (2000) went on to update and revalidate the scale. Reliability testing, using Cronbach alpha correlations, was performed utilizing a sample of i,772 individuals. The SRRS is normally used today.

| [Skip Table] | |

| Life event | Score |

|---|---|

| Death of spouse | 100 |

| Divorce | 73 |

| Marital separation from mate | 65 |

| Detention in jail, other establishment | 63 |

| Death of a close family member | 63 |

| Major personal injury or disease | 53 |

| Marriage | 50 |

| Fired from work | 47 |

| Marital reconciliation | 45 |

| Retirement | 45 |

| Major change in the health or behaviour of a family member | 44 |

| Pregnancy | twoscore |

| Sexual difficulties | 39 |

| Gaining a new family unit fellow member (east.m., through birth, adoption, oldster moving) | 39 |

| Major business readjustment (eastward.chiliad., merger, reorganization, bankruptcy) | 39 |

| Major change in fiscal status | 38 |

| Decease of close friend | 37 |

| Change to different line of work | 36 |

| Major change in the number of arguments with spouse | 35 |

| Taking out a mortgage or loan for a major purchase | 31 |

| Foreclosure on a mortgage or loan | 30 |

| Major modify in responsibilities at work | 29 |

| Son or daughter leaving dwelling (e.g., marriage, attention university) | 29 |

| Trouble with in-laws | 29 |

| Outstanding personal accomplishment | 28 |

| Spouse offset or ceasing to piece of work exterior the home | 26 |

| Start or ceasing formal schooling | 26 |

| Major modify in living atmospheric condition | 25 |

| Revision of personal habits (dress, manners, associations, etc.) | 24 |

| Trouble with boss | 23 |

| Major change in working hours or conditions | 20 |

| Change in residence | xx |

| Modify to a new school | 20 |

| Major modify in usual blazon and/or amount of recreation | 19 |

| Major change in church activities (a lot more or less than usual) | 19 |

| Major alter in social activities (clubs, dancing, movies, visiting) | 18 |

| Taking out a mortgage or loan for a lesser purchase (e.g., for a automobile, television, freezer) | 17 |

| Major change in sleeping habits | 16 |

| Major change in the number of family unit get-togethers | 15 |

| Major change in eating habits | 15 |

| Vacation | 13 |

| Christmas flavor | 12 |

| Pocket-size violations of the law (due east.1000., traffic tickets) | xi |

| Total | ______ |

You can calculate your score on this scale by adding the total points across each of the events that you have experienced over the past yr. And then employ Table xi.3, "Interpretation of Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale" to decide your likelihood of getting ill.

| [Skip Table] | |

| Number of life-change units | Risk of developing a stress-related illness (%) |

|---|---|

| Less than 150 | thirty |

| 150–299 | 50 |

| More than 300 | 80 |

Although some of the items on the Holmes and Rahe scale are more major, yous tin encounter that even minor stressors add to the full score. Our everyday interactions with the environment that are essentially negative, known as daily hassles, can besides create stress also as poorer health outcomes (Hutchinson & Williams, 2007). Events that may seem rather trivial birthday, such as misplacing our keys, having to reboot our calculator because it has frozen, beingness late for an assignment, or getting cutting off by another machine in rush-hour traffic, can produce stress (Fiksenbaum, Greenglass, & Eaton, 2006). Glaser (1985) found that medical students who were tested during, rather than several weeks before, their schoolhouse examination periods showed lower immune system functioning. Other enquiry has found that fifty-fifty more minor stressors, such equally having to practice math problems during an experimental session, can compromise the immune organization (Cacioppo et al., 1998).

Responses to Stress

Non all people feel and respond to stress in the same way, and these differences tin be important. The cardiologists Meyer Friedman and R. H. Rosenman (1974) were among the first to study the link between stress and center affliction. In their research they noticed that even though the partners in married couples often had similar lifestyles, diet, and do patterns, the husbands nevertheless generally had more eye disease than the wives did. As they tried to explicate the departure, they focused on the personality characteristics of the partners, finding that the husbands were more likely than the wives to reply to stressors with negative emotions and hostility.

Recent research has shown that the strongest predictor of a physiological stress response from daily hassles is the amount of negative emotion that they evoke. People who experience potent negative emotions as a result of everyday hassles, and who answer to stress with hostility, experience more negative wellness outcomes than do those who react in a less negative way (McIntyre, Korn, & Matsuo, 2008; Suls & Bunde, 2005). Williams and his colleagues (2001) found that people who scored high on measures of anger were iii times more probable to suffer from center attacks in comparison to those who scored lower on anger.

On average, men are more likely than women are to respond to stress by activating the fight-or-flight response, which is an emotional and behavioural reaction to stress that increases the readiness for action. The arousal that men experience when they are stressed leads them to either go on the attack, in an aggressive or revenging fashion, or else retreat equally quickly as they can to safety from the stressor. The fight-or-flying response allows men to control the source of the stress if they think they tin can practise so, or if that is non possible, it allows them to save face past leaving the situation. The fight-or-flight response is triggered in men by the activation of the HPA centrality.

Women, on the other paw, are less likely to take a fight-or-flight response to stress. Rather, they are more likely to accept a tend-and-befriend response (Taylor et al., 2000). The tend-and-befriend response is a behavioural reaction to stress that involves activities designed to create social networks that provide protection from threats. This arroyo is also self-protective considering it allows the private to talk to others about her concerns, equally well every bit to exchange resources, such as child care. The tend-and-befriend response is triggered in women by the release of the hormone oxytocin, which promotes affiliation. Overall, the tend-and-befriend response is healthier than the flight-or-flight response because it does not produce the elevated levels of arousal related to the HPA, including the negative results that accompany increased levels of cortisol. This may aid explicate why women, on average, have less heart disease and live longer than men.

Managing Stress

No thing how healthy and happy nosotros are in our everyday lives, there are going to be times when we experience stress. Merely we do non need to throw up our easily in despair when things go incorrect; rather, we can utilise our personal and social resource to aid us.

Peradventure the most common approach to dealing with negative affect is to attempt to suppress, avoid, or deny information technology. You lot probably know people who seem to exist stressed, depressed, or broken-hearted, but they cannot or will non meet it in themselves. Perhaps you tried to talk to them about it, to get them to open upwardly to you, but were rebuffed. They seem to act every bit if at that place is no problem at all, but moving on with life without admitting or even trying to deal with the negative feelings. Or perhaps y'all take even taken a similar approach yourself. Have you always had an of import test to written report for or an of import job interview coming up, and rather than planning and preparing for it, y'all simply tried to put it out of your mind entirely?

Research has found that ignoring stress is not a good approach for coping with it. For one, ignoring our bug does not make them go abroad. If we experience so much stress that we go sick, these events will be detrimental to our life even if we do non or cannot acknowledge that they are occurring. Suppressing our negative emotions is likewise non a very good selection, at least in the long run, because it tends to fail (Gross & Levenson, 1997). For one, if we know that we take that large exam coming upward, we accept to focus on the exam itself to suppress it. We can't actually suppress or deny our thoughts, because we actually take to recall and face the issue to make the attempt to not think about it. Doing so takes effort, and nosotros get tired when we try to do it. Furthermore, we may continually worry that our attempts to suppress volition fail. Suppressing our emotions might work out for a brusque while, but when nosotros run out of energy the negative emotions may shoot back up into consciousness, causing united states to reexperience the negative feelings that we had been trying to avoid.

Daniel Wegner and his colleagues (Wegner, Schneider, Carter, & White, 1987) directly tested whether people would be able to effectively suppress a uncomplicated idea. He asked them to not call back almost a white bear for five minutes but to band a bell in case they did. (Effort it yourself; can you practise it?) Even so, participants were unable to suppress the thought as instructed. The white bear kept popping into mind, even when the participants were instructed to avert thinking most it. You lot might have had this feel when you were dieting or trying to study rather than party; the chocolate bar in the kitchen chiffonier and the fun time you were missing at the party kept popping into heed, disrupting you.

Suppressing our negative thoughts does not work, and there is show that the opposite is true: when we are faced with troubles, it is healthy to let out the negative thoughts and feelings past expressing them, either to ourselves or to others. James Pennebaker and his colleagues (Pennebaker, Colder, & Precipitous, 1990; Watson & Pennebaker, 1989) have conducted many correlational and experimental studies that demonstrate the advantages to our mental and physical health of opening upwardly versus suppressing our feelings. This research team has institute that but talking about or writing almost our emotions or our reactions to negative events provides substantial wellness benefits. For instance, Pennebaker and Beall (1986) randomly assigned students to write about either the nearly traumatic and stressful outcome of their lives or trivial topics. Although the students who wrote most the traumas had higher claret pressure and more negative moods immediately afterward they wrote their essays, they were too less probable to visit the student health centre for illnesses during the following six months. Other research studied individuals whose spouses had died in the previous year, finding that the more they talked about the death with others, the less likely they were to get sick during the subsequent year. Daily writing well-nigh one's emotional states has also been plant to increase immune system performance (Petrie, Fontanilla, Thomas, Berth, & Pennebaker, 2004).

Opening upwards probably helps in various ways. For one, expressing our problems to others allows us to gain data, and possibly support, from them (recollect the tend-and-befriend response that is and then effectively used to reduce stress by women). Writing or thinking virtually i's experiences also seems to assistance people make sense of these events and may give them a feeling of control over their lives (Pennebaker & Stone, 2004).

Information technology is easier to respond to stress if we tin interpret it in more positive ways. Kelsey et al. (1999) plant that some people interpret stress as a challenge (something that they feel that they can, with endeavor, bargain with), whereas others see the same stress equally a threat (something that is negative and to be feared). People who viewed stress as a challenge had fewer physiological stress responses than those who viewed it as a threat — they were able to frame and react to stress in more positive ways.

Emotion Regulation

Emotional responses such every bit the stress reaction are useful in warning us about potential danger and in mobilizing our response to it, and then it is a expert matter that we accept them. Still, nosotros also need to learn how to command our emotions, to prevent them from letting our behaviour get out of command. The ability to successfully command our emotions is known as emotion regulation.

Emotion regulation has some important positive outcomes. Consider, for instance, research past Walter Mischel and his colleagues. In their studies, they had four- and five-year-old children sit at a tabular array in front end of a yummy snack, such as a chocolate flake cookie or a marshmallow. The children were told that they could consume the snack right abroad if they wanted. Even so, they were also told that if they could wait for merely a couple of minutes, they'd be able to have two snacks — both the one in forepart of them and another only like it. However, if they ate the one that was in front of them before the time was up, they would not become a 2d.

Mischel found that some children were able to override the impulse to seek immediate gratification to obtain a greater reward at a later time. Other children, of course, were not; they simply ate the first snack right away. Furthermore, the inability to delay gratification seemed to occur in a spontaneous and emotional manner, without much idea. The children who could non resist simply grabbed the cookie because information technology looked so yummy, without being able to stop themselves (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999; Strack & Deutsch, 2007).

The ability to regulate our emotions has important consequences later in life. When Mischel followed up on the children in his original study, he establish that those who had been able to cocky-regulate grew upward to have some highly positive characteristics: They got ameliorate university admission examination scores, were rated by their friends as more socially proficient, and were found to cope with frustration and stress ameliorate than those children who could not resist the tempting cookie at a immature historic period. Thus constructive self-regulation tin be recognized as an important key to success in life (Ayduk et al., 2000; Eigsti et al., 2006; Mischel & Ayduk, 2004).

Emotion regulation is influenced by torso chemicals, particularly the neurotransmitter serotonin. Preferences for small, firsthand rewards over large but after rewards have been linked to low levels of serotonin in animals (Bizot, Le Bihan, Peuch, Hamon, & Thiebot, 1999; Liu, Wilkinson, & Robbins, 2004), and depression levels of serotonin are tied to violence and impulsiveness in human suicides (Asberg, Traskman, & Thoren, 1976).

Inquiry Focus: Emotion Regulation Takes Try

Emotion regulation is specially difficult when we are tired, depressed, or anxious, and it is nether these conditions that we more easily permit our emotions become the best of us (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). If you are tired and worried near an upcoming test, you may find yourself getting angry and taking it out on your roommate, even though she really hasn't done annihilation to deserve it and yous don't actually desire to exist angry at her. It is no secret that nosotros are more probable fail at our diets when we are under a lot of stress, or at night when we are tired.

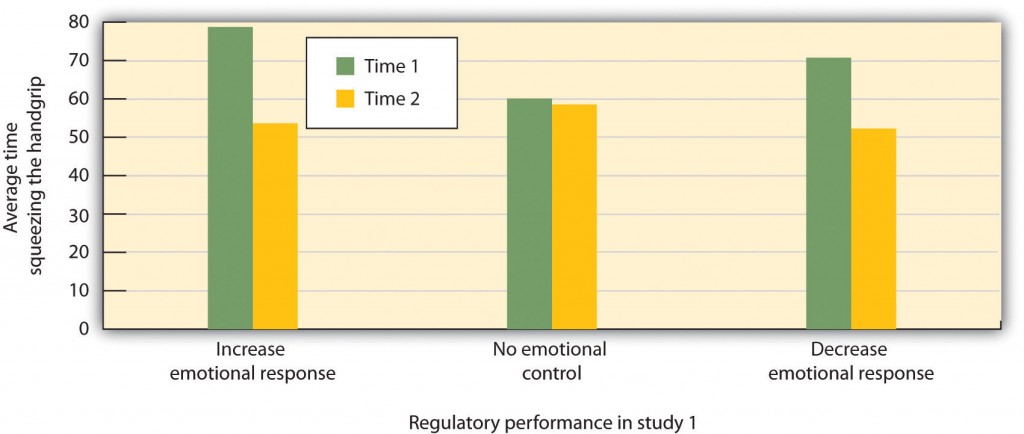

Muraven, Tice, and Baumeister (1998) conducted a study to demonstrate that emotion regulation — that is, either increasing or decreasing our emotional responses — takes work. They speculated that self-command was like a muscle; it merely gets tired when it is used too much. In their experiment they asked participants to watch a brusque movie about environmental disasters involving radioactive waste and their negative effects on wildlife. The scenes included sick and dying animals and were very upsetting. According to random consignment to status, one grouping (the increase emotional response status) was told to actually get into the movie and to express their emotions, one group was to concur back and decrease their emotional responses (the decrease emotional response status), and the 3rd (control) group received no emotional regulation instructions.

Both before and afterward the movie, the experimenter asked the participants to engage in a measure of physical force past squeezing equally hard as they could on a handgrip exerciser, a device used for strengthening hand muscles. The experimenter put a slice of newspaper in the grip and timed how long the participants could hold the grip together before the newspaper fell out. Figure 11.9, "Research Results," shows the results of this study. Information technology seems that emotion regulation does indeed take effort, because the participants who had been asked to command their emotions showed significantly less ability to squeeze the handgrip after the movie than they had showed before it, whereas the control grouping showed virtually no decrease. The emotion regulation during the movie seems to take consumed resources, leaving the participants with less chapters to perform the handgrip job.

In other studies, people who had to resist the temptation to eat chocolates and cookies, who made important decisions, or who were forced to adapt to others all performed more poorly on subsequent tasks that took energy, including giving upward on tasks earlier and declining to resist temptation (Vohs & Heatherton, 2000).

Can we ameliorate our emotion regulation? Information technology turns out that training in self-regulation — just similar physical training — tin can help. Students who practised doing difficult tasks, such as exercising, fugitive swearing, or maintaining good posture, were later constitute to perform better in laboratory tests of emotion regulation such as maintaining a diet or completing a puzzle (Baumeister, Gailliot, DeWall, & Oaten, 2006; Baumeister, Schmeichel, & Vohs, 2007; Oaten & Cheng, 2006).

Primal Takeaways

- Stress refers to the physiological responses that occur when an organism fails to respond accordingly to emotional or physical threats.

- The full general adaptation syndrome refers to the three distinct phases of physiological change that occur in response to long-term stress: alarm, resistance, and burnout.

- Stress is normally adaptive because it helps us respond to potentially dangerous events by activating the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system. But the experience of prolonged stress has a directly negative influence on our physical health.

- Chronic stress is a major contributor to heart illness. It also decreases our power to fight off colds and infections.

- Stressors can occur equally a consequence of both major and pocket-sized everyday events.

- Men tend to answer to stress with the fight-or-flight response, whereas women are more likely to take a tend-and-befriend response.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Consider a time when you experienced stress and how y'all responded to information technology. Do y'all now take a better agreement of the dangers of stress? How will yous change your coping mechanisms based on what you lot have learned?

- Are you proficient at emotion regulation? Can you think of a time when your emotions got the better of you? How might yous make better utilise of your emotions?

References

Asberg, M., Traskman, 50., & Thoren, P. (1976). 5-HIAA in the cerebrospinal fluid: A biochemical suicide predictor?Athenaeum of General Psychiatry, 33(10), 1193–1197.

Ayduk, O., Mendoza-Denton, R., Mischel, Westward., Downey, G., Peake, P. 1000., & Rodriguez, M. (2000). Regulating the interpersonal self: Strategic self-regulation for coping with rejection sensitivity.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(v), 776–792.

Baumeister, R. F., Gailliot, Grand., DeWall, C. N., & Oaten, M. (2006). Cocky-regulation and personality: How interventions increment regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of traits on beliefs.Journal of Personality, 74(half-dozen), 1773–1801.

Baumeister, R. F., Schmeichel, B., & Vohs, M. D. (2007). Self-regulation and the executive office: The cocky as controlling agent. In A. Due west. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (Eds.),Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (Vol. 2). New York, NY: Guilford Printing.

Bizot, J.-C., Le Bihan, C., Peuch, A. J., Hamon, M., & Thiebot, M.-H. (1999). Serotonin and tolerance to filibuster of advantage in rats.Psychopharmacology, 146(4), 400–412.

Cacioppo, J. T., Berntson, Yard. G., Malarkey, W. B., Kiecolt-Glaser, J. M., Sheridan, J. F., Poehlmann, K. One thousand.,…Glaser, R. (1998). Autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immune responses to psychological stress: The reactivity hypothesis. InRegister of the New York Academy of Sciences: Neuroimmunomodulation: Molecular aspects, integrative systems, and clinical advances (Vol. 840, pp. 664–673). New York, NY: New York Academy of Sciences.

Canadian Mental Wellness Association. (2014). Post traumatic stress disorder. Retrieved 2014 from http://www.cmha.bc.ca/get-informed/mental-health-information/ptsd

Cohen, S., & Herbert, T. B. (1996). Wellness psychology: Psychological factors and physical disease from the perspective of homo psychoneuroimmunology.Annual Review of Psychology, 47, 113–142.

Dekker, M., Koper, J., van Aken, Thou., Pols, H., Hofman, A., de Jong, F.,…Tiemeier, H. (2008). Salivary cortisol is related to atherosclerosis of carotid arteries.Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 93(x), 3741.

Eigsti, I.-M., Zayas, 5., Mischel, Westward., Shoda, Y., Ayduk, O., Dadlani, Chiliad. B.,…Casey, B. J. (2006). Predicting cognitive control from preschool to late adolescence and immature adulthood.Psychological Science, 17(6), 478–484.

Epel, Eastward., Lin, J., Wilhelm, F., Wolkowitz, O., Cawthon, R., Adler, N.,…Blackburn, E. H. (2006). Prison cell aging in relation to stress arousal and cardiovascular disease take a chance factors.Psychoneuroendocrinology, 31(3), 277–287.

Faulkner, Southward., & Smith, A. (2009). A prospective diary study of the office of psychological stress and negative mood in the recurrence of canker simplex virus (HSV1).Stress and Health: Periodical of the International Guild for the Investigation of Stress, 25(ii), 179–187.

Fiksenbaum, L. One thousand., Greenglass, E. R., & Eaton, J. (2006). Perceived social support, hassles, and coping among the elderly.Periodical of Applied Gerontology, 25(one), 17–30.

Friedman, M., & Rosenman, R. H. (1974).Type A behavior and your heart. New York, NY: Knopf.

Glaser, R. (1985). Stress-related impairments in cellular immunity.Psychiatry Inquiry, 16(3), 233–239.

Gross, J. J., & Levenson, R. Westward. (1997). Hiding feelings: The acute effects of inhibiting negative and positive emotion.Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(ane), 95–103.

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale.Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213–218.

Hutchinson, J. 1000., & Williams, P. Yard. (2007). Neuroticism, daily hassles, and depressive symptoms: An examination of moderating and mediating effects.Personality and Individual Differences, 42(vii), 1367–1378.

Kelsey, R. M., Blascovich, J., Tomaka, J., Leitten, C. 50., Schneider, T. R., & Wiens, S. (1999). Cardiovascular reactivity and accommodation to recurrent psychological stress: Effects of prior task exposure.Psychophysiology, 36(half dozen), 818–831.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. Thousand., McGuire, L., Robles, T. F., & Glaser, R. (2002). Psychoneuroimmunology: Psychological influences on allowed function and health.Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 70(3), 537–547.

Krantz, D. S., & McCeney, M. 1000. (2002). Effects of psychological and social factors on organic illness: A critical assessment of enquiry on coronary heart illness.Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 341–369.

Liu, Y. P., Wilkinson, L. Southward., & Robbins, T. Due west. (2004). Effects of acute and chronic buspirone on impulsive choice and efflux of five-HT and dopamine in hippocampus, nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex.Psychopharmacology, 173(ane–2), 175–185.

McIntyre, K., Korn, J., & Matsuo, H. (2008). Sweating the small stuff: How different types of hassles result in the experience of stress.Stress & Health: Journal of the International Social club for the Investigation of Stress, 24(5), 383–392.

Metcalfe, J., & Mischel, W. (1999). A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: Dynamics of willpower.Psychological Review, 106(1), 3–19.

Miller, G., Chen, E., & Cole, S. Westward. (2009). Health psychology: Developing biologically plausible models linking the social world and physical health.Almanac Review of Psychology, 60, 501–524.

Mischel, W., & Ayduk, O. (Eds.). (2004).Willpower in a cognitive-melancholia processing system: The dynamics of filibuster of gratification. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resource: Does cocky-command resemble a musculus?Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 247–259.

Muraven, G., Tice, D. Thou., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Self-control as a limited resource: Regulatory depletion patterns.Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 74(3), 774–789.

Oaten, Grand., & Cheng, K. (2006). Longitudinal gains in self-regulation from regular concrete do.British Journal of Health Psychology, 11(4), 717–733.

Pennebaker, J. W., & Beall, S. One thousand. (1986). Against a traumatic result: Toward an understanding of inhibition and disease.Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(iii), 274–281.

Pennebaker, J. W., & Stone, L. D. (Eds.). (2004).Translating traumatic experiences into language: Implications for child corruption and long-term health. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Pennebaker, J. West., Colder, M., & Sharp, L. G. (1990). Accelerating the coping procedure.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(3), 528–537.

Petrie, K. J., Fontanilla, I., Thomas, Thousand. G., Berth, R. J., & Pennebaker, J. Due west. (2004). Effect of written emotional expression on immune function in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: A randomized trial.Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(ii), 272–275.

Pulcino, T., Galea, Southward., Ahern, J., Resnick, H., Foley, M., & Vlahov, D. (2003). Posttraumatic stress in women afterwards the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City.Journal of Women's Wellness, 12(eight), 809–820.

Rahe, R. H., Veach, T. 50.,Tolles, Robbyn L., and Murakami, 1000. (2000). The stress and coping inventory: an educational and research musical instrument. Stress Medicine, xvi(four), p.199–208.

Rahe, R. H., Mahan, J., Arthur, R. J., & Gunderson, Eastward. Yard. Due east. (1970). The epidemiology of disease in naval environments: I. Illness types, distribution, severities and relationships to life change.Armed services Medicine, 135, 443–452.

Rodrigues, S. M., LeDoux, J. East., & Sapolsky, R. Chiliad. (2009). The influence of stress hormones on fear circuitry.Annual Review of Neuroscience, 32, 289–313.

Selye, H. (1936). A syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents [PDF].Nature, 138, 32. Retrieved from http://neuro.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/x/two/230a.pdf

Selye, H. (1956).The stress of life. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Selye, H. (1974). 40 years of stress inquiry: Main remaining issues and misconceptions.Canadian Medical Clan Periodical, 115(1), 53–56.

Selye, H. (1982). The nature of stress. Retrieved from http://www.icnr.com/manufactures/thenatureofstress.html

Strack, F., & Deutsch, R. (2007). The function of impulse in social behavior. In A. West. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (Eds.),Social Psychology: Handbook of Bones Principles (Vol. two). New York, NY: Guilford Printing.

Suls, J., & Bunde, J. (2005). Anger, anxiety, and depression every bit hazard factors for cardiovascular disease: The problems and implications of overlapping affective dispositions.Psychological Bulletin, 131(2), 260–300.

Taylor, S. Eastward., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A. R., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, non fight-or-flight.Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429.

Uchino, B. Due north., Smith, T. W., Holt-Lunstad, J., Campo, R., & Reblin, M. (2007). Stress and illness. In J. T. Cacioppo, Fifty. Yard. Tassinary, & G. G. Berntson (Eds.),Handbook of psychophysiology (3rd ed., pp. 608–632). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Vohs, K. D., & Heatherton, T. F. (2000). Cocky-regulatory failure: A resource-depletion approach.Psychological Science, eleven(three), 249–254.

Watson, D., & Pennebaker, J. W. (1989). Health complaints, stress, and distress: Exploring the fundamental function of negative affectivity.Psychological Review, 96(two), 234–254.

Wegner, D. M., Schneider, D. J., Carter, S. R., & White, T. L. (1987). Paradoxical effects of thought suppression.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(1), 5–13.

Wells, West. (2006). How chronic stress exacerbates cancer.Journal of Cell Biology, 174(4), 476.

Williams, R. B. (2001). Hostility: Effects on health and the potential for successful behavioral approaches to prevention and treatment. In A. Baum, T. A. Revenson, & J. Eastward. Singer (Eds.),Handbook of wellness psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Long Description

Figure 11.7 long description: Stages of Stress as identified by Hans Selye. Stage 1: General alarm reaction. The first reaction to stress. The trunk releases stress hormones, including cortisol. Stage 2: Resistance. After a flow of chronic stress the body adapts to the ongoing threat and tries to return to normal functions. Glucose levels increase to sustain energy, and claret pressure increases. Phase 3: Exhaustion. In this stage, the body has run out of its reserves of energy and immunity. Claret sugar levels decrease, leading to decreased stress tolerance, progressive mental and physical burnout, illness, and collapse. The body's organs brainstorm to fail, and eventually illness or death occurs. [Return to Figure xi.7]

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontopsychology/chapter/10-2-stress-the-unseen-killer/

0 Response to "according to hans selye, what happens when an animal is alarmed?"

Post a Comment